.

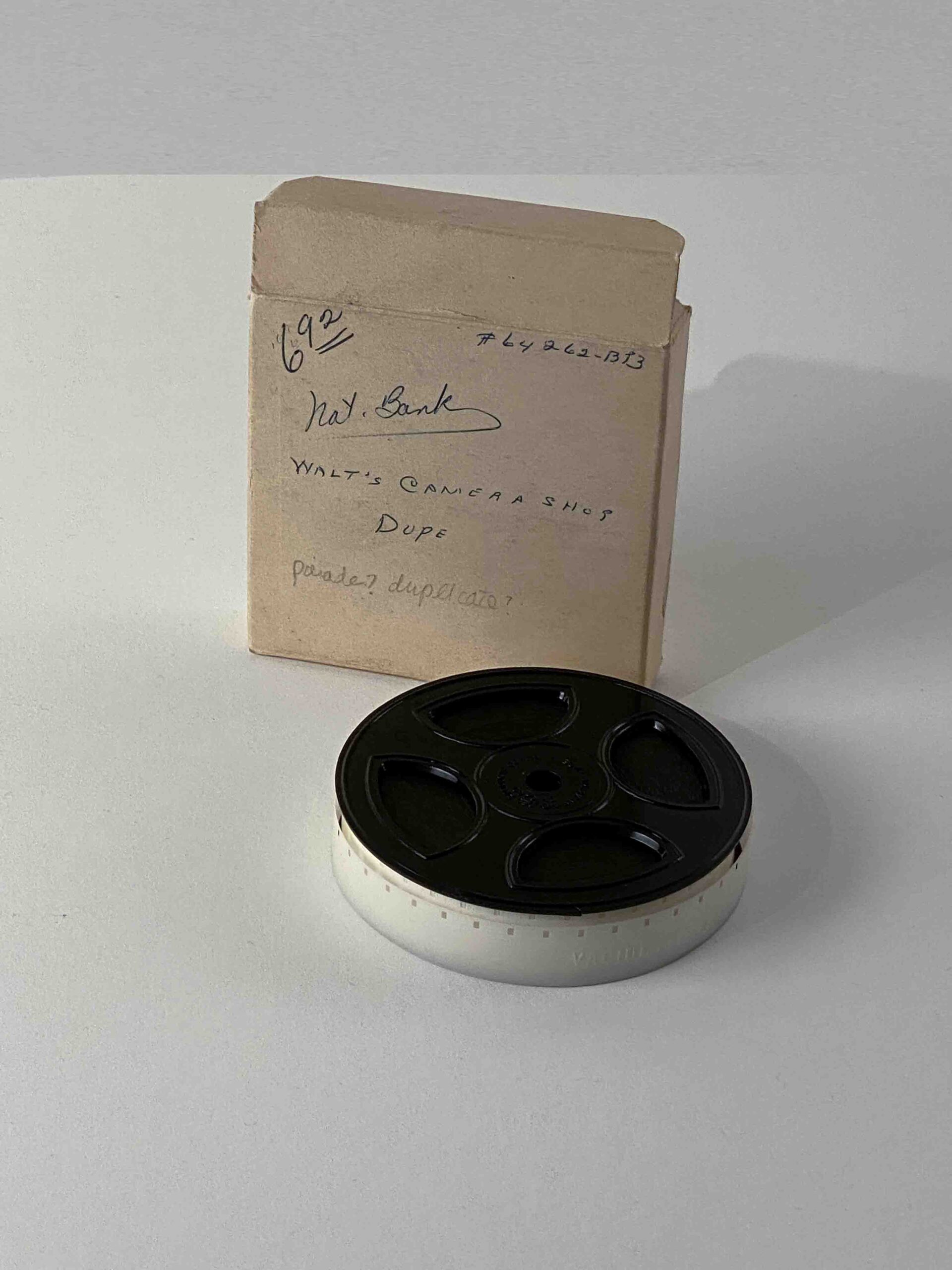

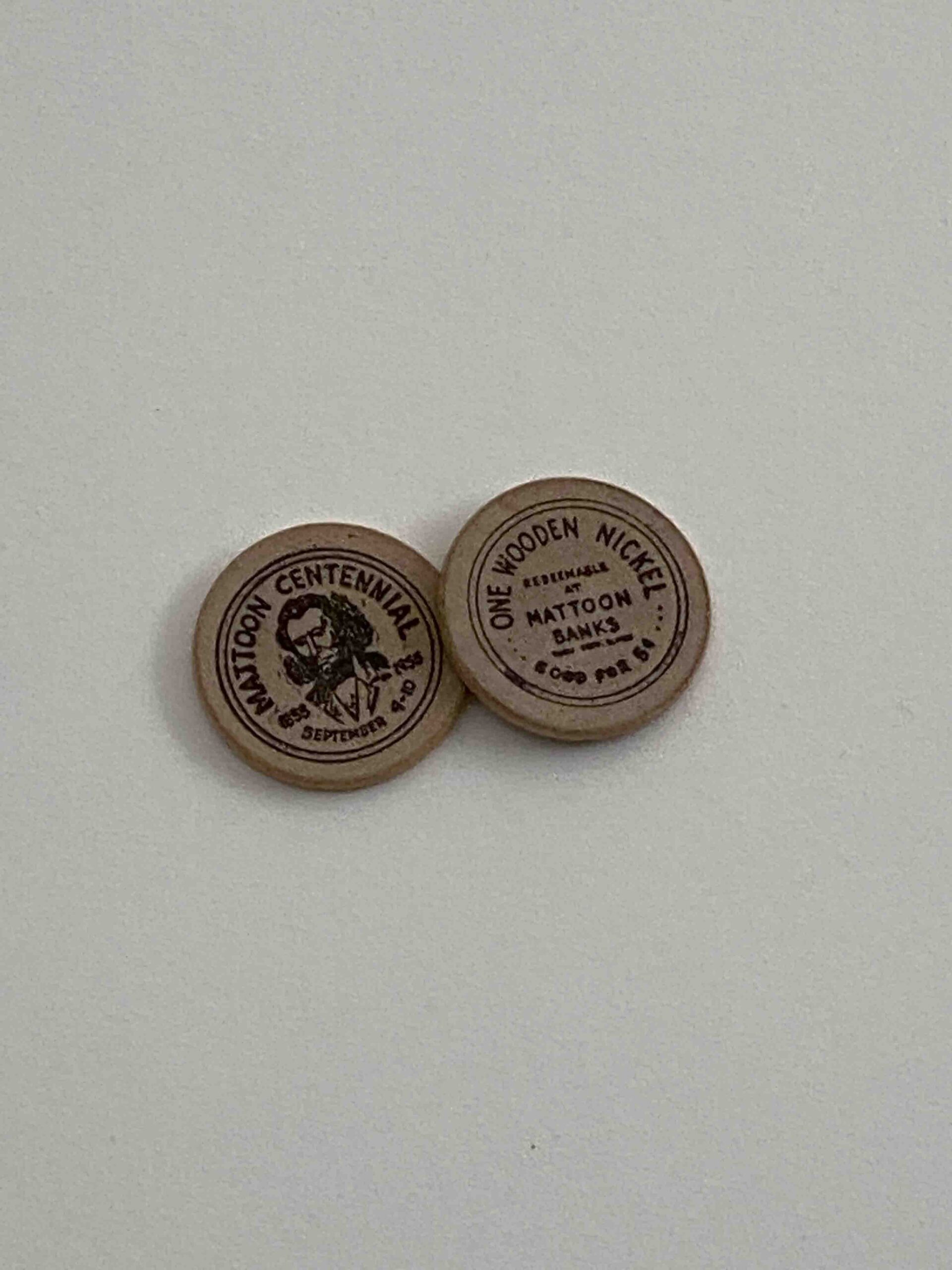

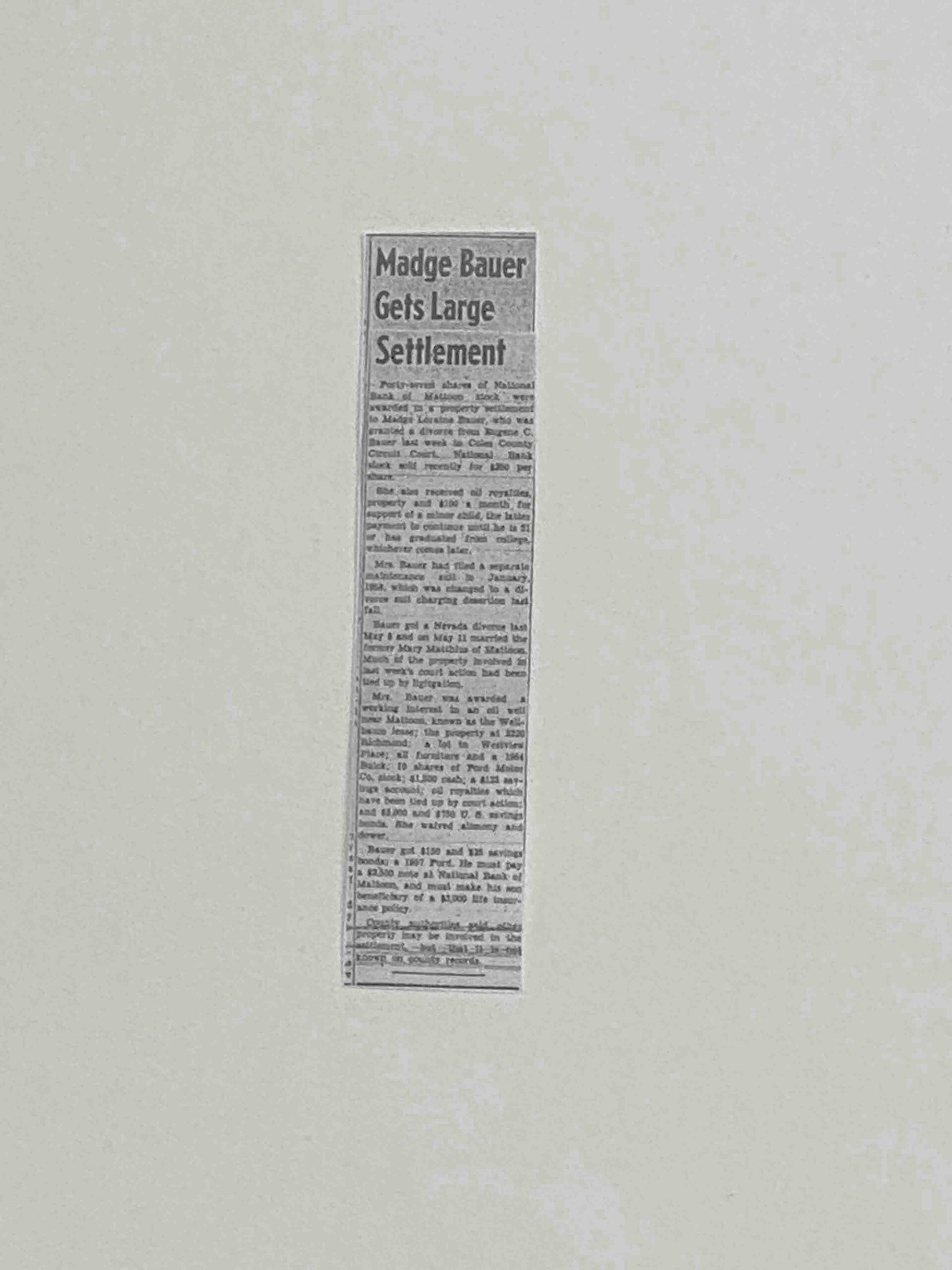

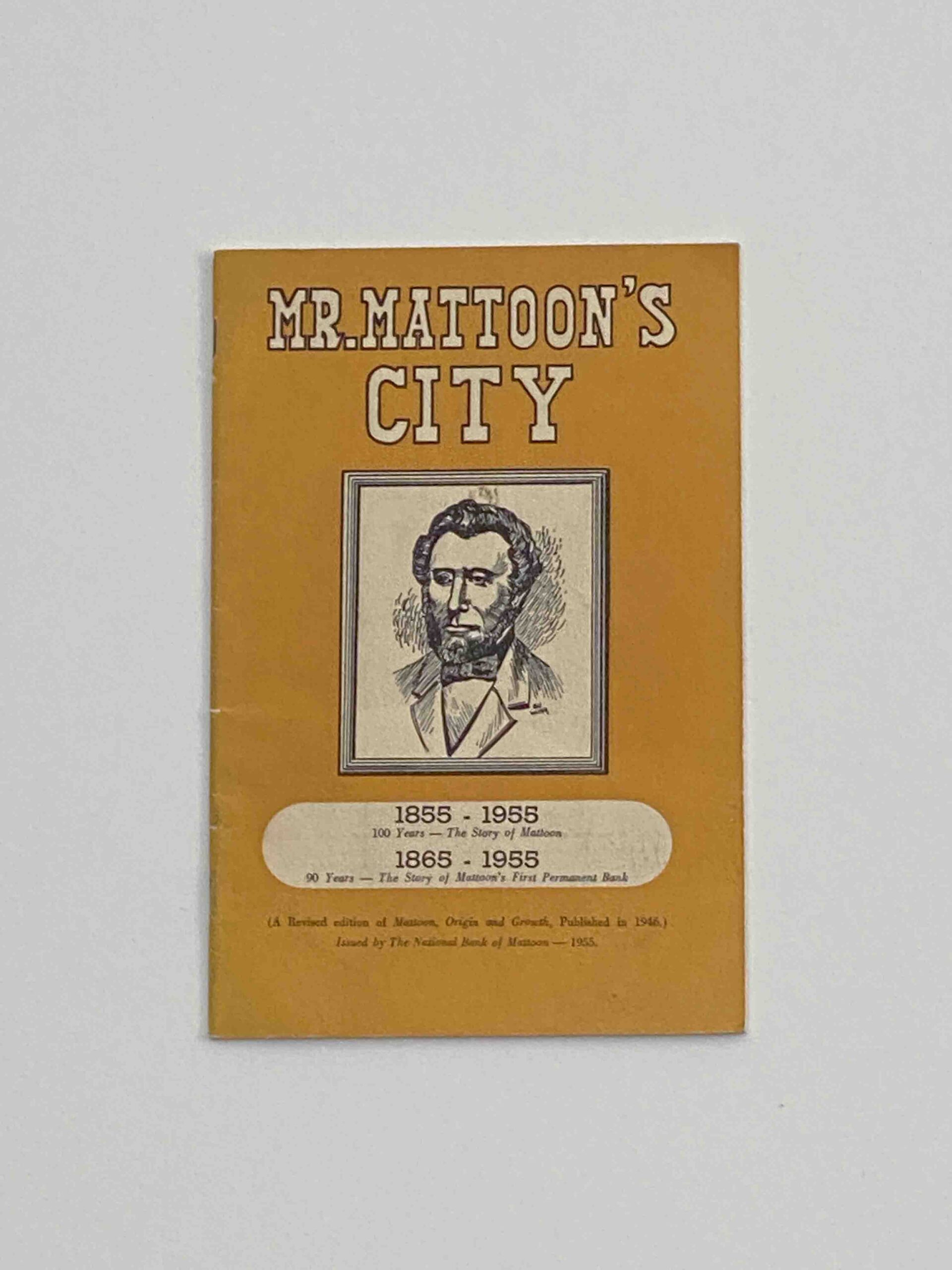

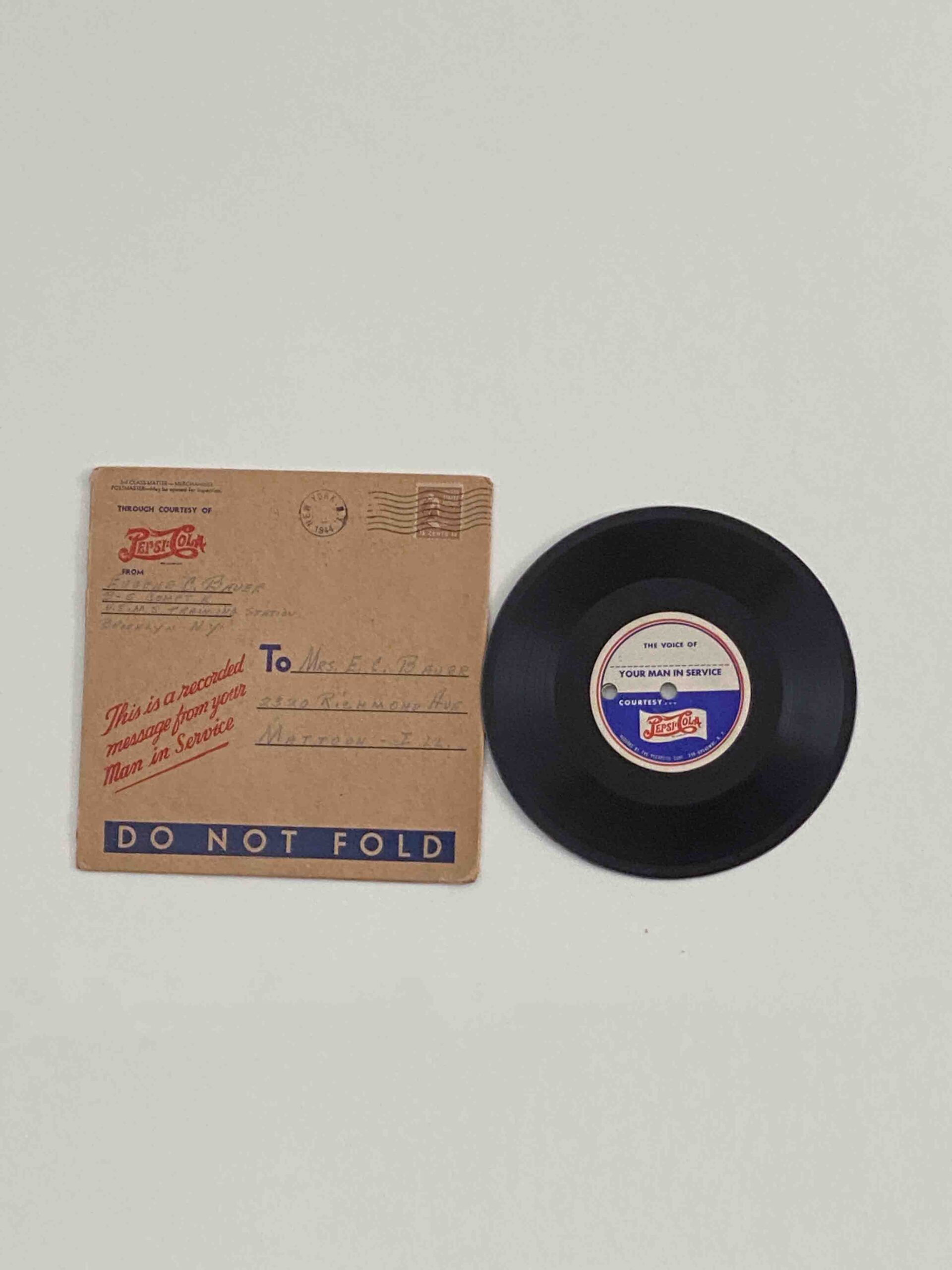

In an expanded field of documentary, this project is an

excavation of materials and an

assembly of an archive. Through

objects, memories and stories, I explore my grandparents’ lives

to find where their personal histories intersect with the

collective.

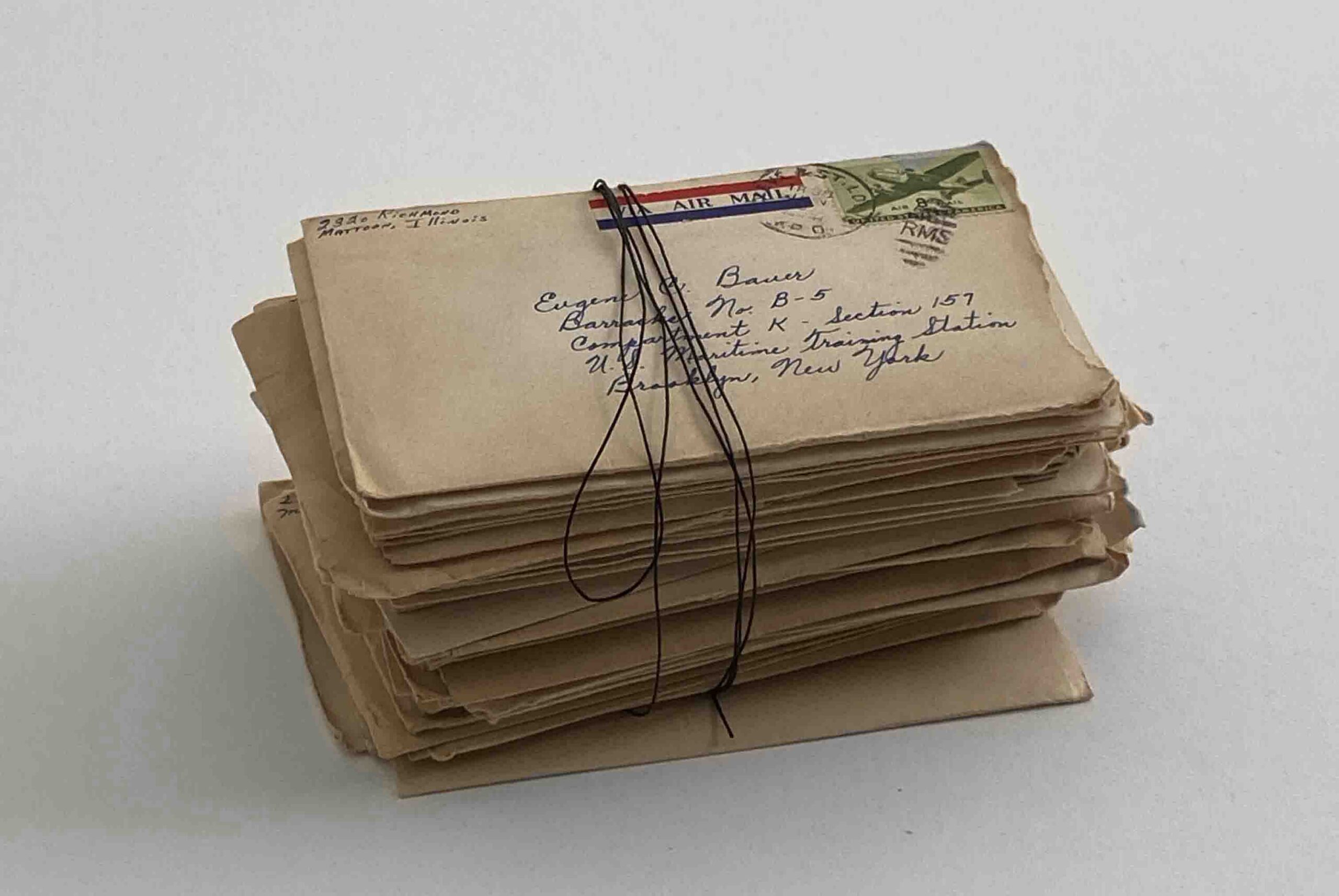

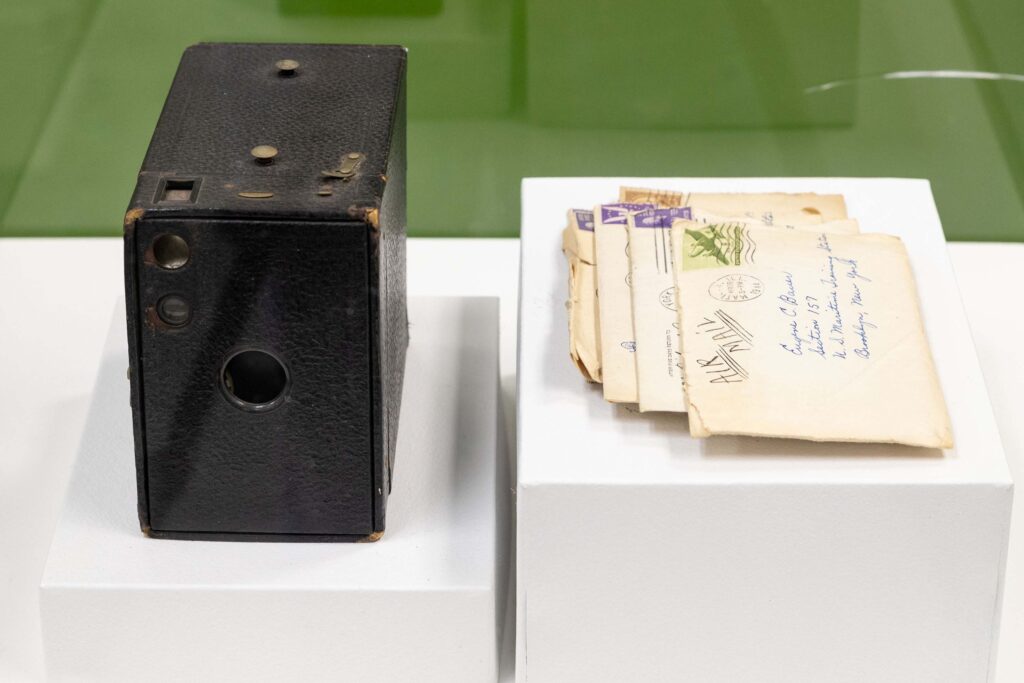

I pull

letters, photos, and objects from this

archive and then

select, curate, maintain and arrange them like a

miniature museum.

Indexical portraits and

readymade works of art, the

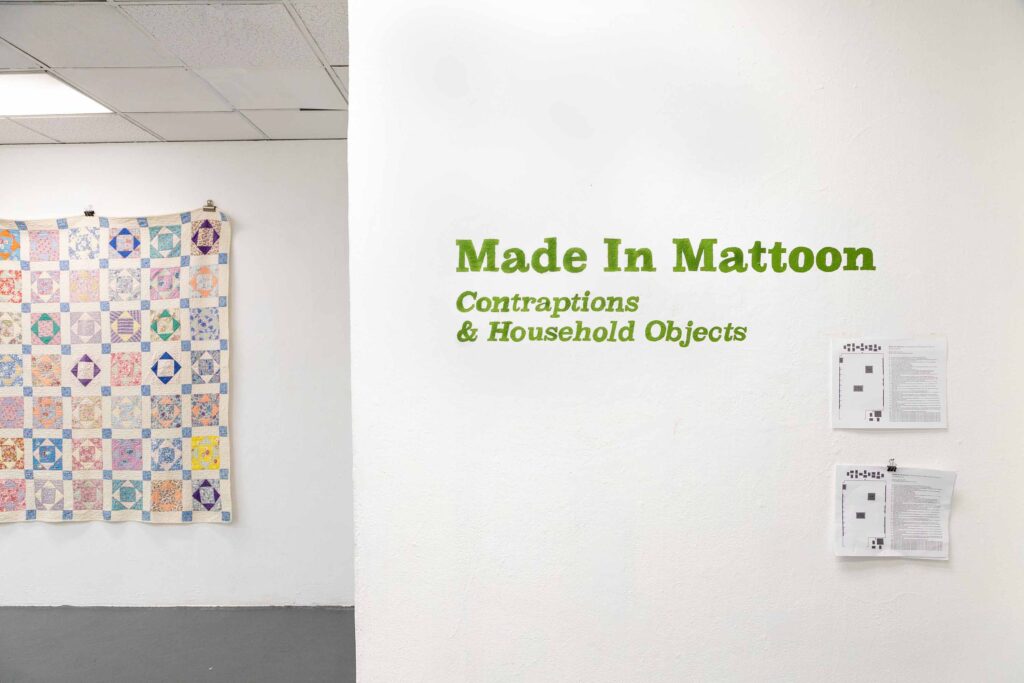

white gallery space of A402

isolates and delineates every form for this installation.

.

Through a circuitous, meandering tour of the

individual items, without the benefit of

being anchored to a specific narrative, the viewer is left to

question what the relationships are

between the objects.

These items become launchpads to stories I share in a

hybrid documentary (working title: Made In Mattoon, still in process).

Both the installation and the film hold

distinctly different spaces for the

past and present,

micro and macro

worlds suspended

within the imagination.

.